“That’s your real job!?”

I’m often met with that response when I tell people that triathlon is my full-time occupation. Professional triathletes are a rare breed. Worldwide, there are probably fewer than a thousand of us earning any significant money from the sport and a much smaller fraction truly earning a living by scampering around in spandex.

Pro triathlon is far from the easiest of career paths. Even in my most financially successful year, my hourly rate factoring in all my triathlon-related activities would be well below minimum wage. I may not have to punch in to start my workday, but that’s because I’m never really off the clock, with every single minute and decision impacting my performance. I can also forget about job security and biweekly paychecks, late nights and sleep-ins, hookers and blow, socials and speakeasies.

However, the fringe benefits can’t be beaten. Gallivanting about the globe on sponsors’ dime, chasing glory and gorgeous people, honing the weapons that are my body and mind, decked out in the blingiest of crabon fibré, answerable to no one but myself, etc., etc. And let’s not forget the naps, the decadent daily naps…

… Okay, maybe it’s not quite all that glamorous.

Every year of my pro triathlon career, I’ve shared a detailed look at my annual triathlon budget. Here you’ll find the third edition. In addition to a breakdown of income and expenses, I’ll also touch on a few related subjects. If you haven’t already read my first and second year budgets, or could use a refresher, I recommend starting there. As always, my intent is to inform and hopefully to entertain!

Related: My rookie pro triathlon budget, My second year pro triathlon budget

2016 budget summary

By all measures, my third professional season was my most successful year. I tackled nine long course races and managed to collect a prize money paycheck at all of them, including Ironman 70.3 wins number two and three of my career. Coupled with increasing sponsorship, it was my best financial year to date.

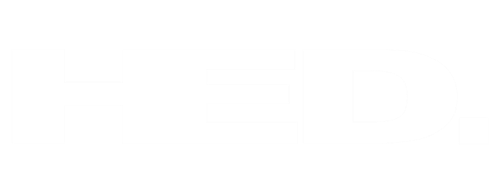

Revenue, expenses and earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) from triathlon over my three years as a professional are summarized below. Throughout this post, I’ll present dollar figures in both Canadian and US dollars (CA$/US$, converted at the average annual exchange rate) since the majority of my revenue and expenses are in US dollars though I live and pay taxes in Canada.

| 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triathlon revenue | CA$59,076

US$44,619 |

CA$38,288

US$30,030 |

CA$11,090

US$10,047 |

| Triathlon expenses | CA$14,976

US$11,311 |

CA$15,559

US$12,203 |

CA$9,544

US$8,646 |

| Earnings (EBIT) | CA$44,100

US$33,308 |

CA$22,729

US$17,827 |

CA$1,546

US$1,400 |

Notable numbers

Before revealing le budget, here are some interesting figures from 2016:

- 8 Ironman 70.3 races + 1 ITU Long Distance World Championships

- US$3,350 – average prize money per race (ranging from $750 to $6,000)

- CA$414 – average out-of-pocket expenses per race including airfare, car rentals, gas, accommodations and meals (ranging from $21 to $1,115)

- CA$1,082 spent on hotels

- CA$993 spent on meals and groceries while traveling

- CA$2,288 spent on airfare and baggage fees (Many flights were generously covered by Keystone Communications/Giles Atkinson and Randy Stanfield.)

- ZERO spent on airline bike fees

- ZERO spent on physiotherapy, massage or medical treatment

The 2016 Budget

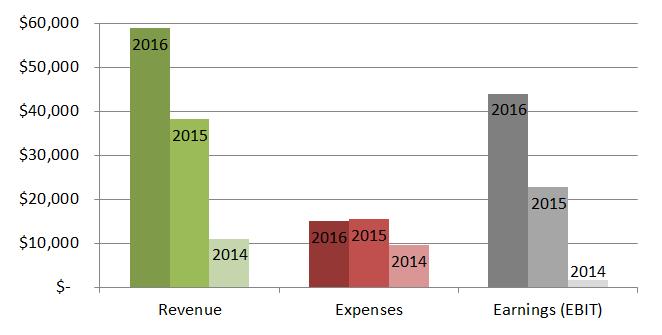

Like my previous budgets, this one strictly includes triathlon-related revenue and expenses, and not my living expenses or my very modest earnings from consulting work and investments. However, unlike previous budgets, this year I included the cost of food while on the road for triathlon. I still omitted the considerable cost of food beyond the caloric needs of a NARP (non-athletic regular person).

Totaling up expenses, I’m always floored by how much the multitude of triathlon costs rack up, from that 99¢ gel to that $999 race afterparty flight to Ecuador. This is despite a very budget-conscious approach with scarcely any fat to trim on my budget.

In previous budget posts, I’ve described my minimalist lifestyle which helps make this career sustainable. My dad often chides me for being “pathologically cheap”, but I think “frugal” is a politer term. Outside of triathlon, this was a spendy year for me. While I continued to rent an inexpensive loft in smalltown Ontario (from Mommy & Daddy), there were some major expenses such as my first car (a Toyota Prius C, arguably a business expense) and saving up to purchase my first house. Offsetting this, I spent a grand total of $0 on Ironman merchandise and tattoos (such restraint!), $8 on booze, $10 on movies and just a little on clothes in 2016.

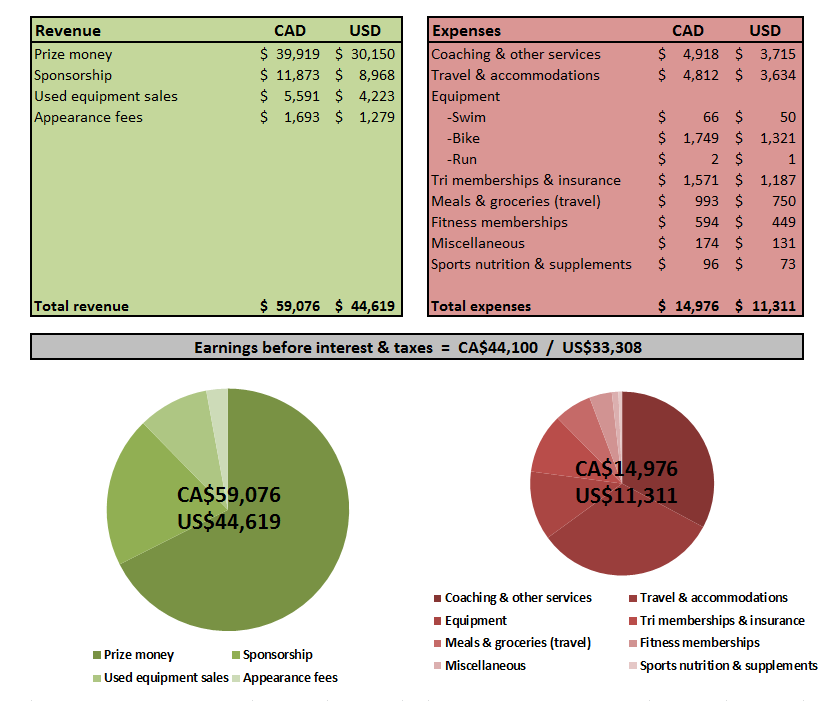

Prize Money

For the third year, the majority of my triathlon income came from prize money (US$30,150 / 68%), broken down by race below. This amount was up from the previous year (US$25,500 / 85%), but accounted for a smaller fraction of total revenue. I raced eight Ironman 70.3 races plus the ITU Long Distance World Championships between March and late October, my longest season ever. If it weren’t for the stressful and disruptive process of house hunting this fall, I would have done a tenth race in December.

- US$750 – 7th at Ironman 70.3 Monterrey (Excuse alert—mechanical issues!)

- US$1,500 – 7th at the Ironman 70.3 North American Championship – St. George

- US$3,000 – 4th at Ironman 70.3 Mont Tremblant

- US$3,000 – 4th at Ironman 70.3 Santa Cruz

- US$3,150 – 5th at the ITU Long Distance World Championships

- US$3,250 – 3rd at Ironman 70.3 Los Cabos

- US$4,500 – 3rd at the Ironman 70.3 South American Championship – Palmas

- US$5,000 – 1st at Ironman 70.3 Ecuador

- US$6,000 – 1st at Ironman 70.3 Eagleman

- US$30,150 / CA$39,919 – Total

Podiums and particularly wins are disproportionately lucrative, both in terms of prize money and sponsor bonuses. For example, my wins at Ironman 70.3 Eagleman and Ecuador accounted for 38% of my total revenue for the year.

Sponsorship

Over the course of a pro triathlete’s career, sponsorship will typically account for an increasing fraction of total income. In my rookie season, I didn’t earn a cent from financial sponsorship (excluding in-kind and travel contributions). The following year, about 10% of my income came from cash sponsorship, this year it was 20% and next year will likely be substantially higher. It takes time to build the resume, reputation and connections required to procure solid contracts.

While I can’t divulge details of specific sponsor contracts, I can speak in general terms. One skill I’m mastering in the realm of sponsorship is learning to say “no thanks”. I politely decline far more sponsorship offers than I accept these days. Most simply aren’t a good fit. Some are too demanding. Others undervalue my services. Others lack room to grow. I’ve become quite meticulous about evaluating the companies I work with, from their products, to their employees, to their marketing, to their communication. I ask myself if this a relationship with development potential, one I’ll still be pleased with over the years to come. I’m always aiming for long-term relationships, partly because flipping sponsors too often degrades my value as brand ambassador. I’ve learned how to appraise my value, know my blueprint for an ideal sponsor, write a compelling proposal, drive a hard bargain, and be prepared to walk away from an offer that doesn’t feel right.

Related: Ventum & my quest for a worthy whip

This was the first year that all my sponsor relationships included a financial component, mostly in the form of performance bonuses or appearance fees. That is to say that I didn’t accept any product-only contracts. Generally, I’d rather purchase exactly what I want without any limitations or obligations, rather than settle for subpar sponsorship. This is one reason that I still have a relatively limited number of sponsors and a good deal of my gear is not sponsored.

This coming year, my fourth as a professional, will be the first that most of my contracts will pay a modest salary or stipend. This will be a welcome relief from the tense situation of deriving the vast majority of my income from just a handful of days of racing. More predictable income will also improve cash flow and provide a measure of income security, critical in the event of injury or other unforeseen circumstances impacting my racing. Convincing sponsors to part with cash up front is no mean feat and is the culmination of years of work, trust and experience.

Another recent achievement was adding two new non-endemic sponsorships (i.e. unrelated to triathlon). Companies in the triathlon/endurance sports industry tend to be somewhat limited in their scope, resources and marketing. Companies from other industries are sometimes in a position to offer larger contracts, broader exposure and a refreshing change of pace (such as a recent trip to Taiwan to shoot a commercial).

Taking in the #sunset over #Taichung after a long day of filming. ? ? Wei Chen

A photo posted by Cody Beals (@cody.beals) on

Why don’t I have an agent?

I’ve been repeatedly told that I should get an agent. I hear that agents can open doors and negotiate deals that wouldn’t be available to me as a self-represented athlete. I’ve resisted working with an agent for a few reasons. First of all, I really enjoy the process of courting sponsors, negotiating deals and personally maintaining these relationships. It can sometimes feel like a burden on top of everything else, but I find it rewarding. These business dealings are also developing a skill set that could prove to be useful in my post-racing career. Furthermore, based on the progression in my triathlon finances, I don’t seem to be doing too badly for myself. I haven’t yet seen a compelling case that working with an agent would be worth sacrificing a percentage of my hard-earned contracts. Frankly, there’s not that much to go around!

Pro bono

As a pro triathlete, I’m regularly approached with opportunities to donate my time to various causes, usually through writing, speaking or clinics. Over the years, I’ve benefited tremendously from the generosity of the triathlon community and I’m eager to give back however I can. One example is the countless hours I spend writing replies to the many questions I receive, an activity which is largely invisible to my sponsors and adds nothing to my bottom line. In particular, I do my best to find time for young athletes, beginners and any initiatives that support the growth of the sport. That work is rewarding in ways that money could never match.

“Exposure” is often promised as compensation for unpaid or underpaid work. Exposure is a valuable and important, but it sadly doesn’t pay the bills… at least not directly. There’s a very short list of ways that I can get paid as a pro triathlete: prize money, sponsorship/endorsement, writing, appearances and speaking engagements. That’s about it. In order to make ends meet, my financial reality dictates that I have to be selective about what and how much I give away for free, as much as I’d love to do it all. I know that independent professionals in other sectors—musicians, graphic designers and freelance writers, to name a few—face a similar dilemma.

Government funding

As a long course triathlete, I never have—and almost certainly never will— receive a cent of government funding. Some other countries provide some funding for their long course elite triathletes, though it’s not the norm. In Canada, national and provincial funding programs such as Sport Canada’s Athlete Assistance Program, Own the Podium, and Ontario’s Quest for Gold exclusively target Olympic stream triathletes (i.e. short course/ITU) with the primary objective of converting cash into Olympic medals.

I’m not complaining. I see little reason why taxpayers should fund my lycra-clad escapades, no more than I should foot the bill for your Ironman vacation. In fact, the absence of government funding has its benefits. It has forced me and other full-time non-Olympic stream athletes to cultivate an entrepreneurial streak in order to survive. Successful long course professional triathletes—and I don’t just mean those with great race results—work hard to put themselves out there, build and engage a following, develop a marketable brand and skill set and manage a portfolio of sponsorship contracts. I just don’t see this entrepreneurial drive to the same extent among government-funded athletes, though there are many fine exceptions. In the sink or swim world of pro triathlon, I learned pretty quickly that hacking it demands equal measures of athleticism and business savvy.

Crowdfunding

Crowdfunding is another revenue source that you’ll never see on my balance sheet. I’ve never sought monetary donations from my family, friends or followers, though I’ve benefited greatly from the generosity of the athletic community in other ways. I’ve always felt strongly that I alone should bear the financial responsibility for my decision to pursue professional sport. Achieving financial self-sufficiency and sustainability in my triathlon career was my goal from the get-go. That’s one aspect of my personal definition of being a “professional athlete”. It seems that athletes have been increasingly resorting to crowdfunding to finance their objectives. The public response can be mixed, with such campaigns sometimes prompting ire and ridicule on online forums. Notwithstanding my ethical reservations, my view is that crowdfunding may provide short-term gain for athletes, but it may harm their image to a much greater extent. My two cents: if you’re an adult pursuing elite sport, you should be running your athletic career like a business, not a charity.

Concluding thoughts

Every year I share my finances, I’m met with different reactions. Many are surprised to learn that pro triathlon is not as lucrative as they had imagined. Some veterans will lament the state of the sport. Others will question my sanity for walking away from a dependable career in consulting to wander to the tortuous trail to the heights of triathlon. Still others will be impressed and even envious that I’m able to earn any money at all from this glorified hobby.

Professional triathlon is not without its challenges. From a financial standpoint, it’s taken years of investment and toil to finally reach a relatively comfortable income. It’s still a precarious position that could all come tumbling down due to a few misteps or mishaps. Even so, I consider it a privelege. I didn’t know exactly what I was signing up for when I took my elite card three years ago, but it’s been one hell of an adventure so far. I’m so grateful to all who make it possible from my top sponsors, to my newest followers, to my mentor/coach David Tilbury-Davis, to friends and advisers like Giles Atkinson, Randy Stanfield and John Salt, to all of you who read this far. Thank you!