On August 19th, I made my full distance debut at IRONMAN Mont Tremblant. I felt confident coming off my best training block ever, but equally apprehensive staring down the barrel of my first IRONMAN. Okay, apprehensive is an understatement… It felt like my first race all over again!

I surprised myself as much as everyone else, coming away with a dominant win, bike and overall course records as the first Canadian to win this race. Six weeks later, I backed this up with a second win at IRONMAN Chattanooga, claiming another bike course record (unofficial due to the canceled swim), another fastest run split and securing one of the first qualification slots for the 2019 IRONMAN World Championship.

This post isn’t about how those races played out. That’s been discussed to death in a dozen podcasts and interviews, my race recaps and my “Ask Me Anything” thread on Slowtwitch. Due to popular demand, I’m sharing a detailed look at my prep for those two performances including every single training session over a 15 week period between June 18 and September 30. Publishing such a complete record of training for a world class IRONMAN performance is unprecedented, to the best of my knowledge.

I had three motivations in writing this post. First, I have a reputation for openness and transparency to uphold. Second, I take a collaborative approach to my journey in triathlon and honestly appreciate feedback. Finally, I’m getting sick of replying to the same questions again and again! 😉

I split this post into two parts to spare you an ungodly long read. This first part includes some general comments, context, and explanation of various aspects of my methodology as well as a summary of the training block. The second part (coming soon) gets into the nitty-gritty: details of every single workout during this period without much commentary.

General Comments

Coaching

I’ve worked with David Tilbury-Davis for my entire professional triathlon career (since 2014). Initially, I desperately needed a high degree of oversight after a long history of boneheaded misguided self-coaching. Over the past couple years, I felt ready to accept more control and I resumed writing my own sessions with David’s ongoing mentorship. I appreciate the open, collaborative dynamic we have. I handle the day-to-day details while David concerns himself more with the big picture. He offers advice and a much needed objective perspective, and also helps with analysis, season and race planning, goal setting and research.

Since moving to Guelph, Ontario last year, I’ve also been informally training (mostly swimming) with Craig Taylor’s Guelph Triathlon Project, an ITU focused squad that rose from the ashes of one of Canada’s former national training centers. A special thank you to both David and Craig for permitting me to share a good deal of their workouts and ideas, which I consider their intellectual property.

General Approach

It may surprise you to hear that I rarely planned sessions more than a few days in advance in this block, despite an otherwise meticulous approach. To the casual observer, I appear to be flying by the seat of my pants when it comes to my day-to-day training! That’s only half true. I operate within a loosely planned periodization structure for each block. I have a general sense of what training load, intensity distribution and types of sessions I intend to accomplish. Within a given week, I plan a few key sessions in each discipline. Beyond that, I wake up every day rarely knowing exactly how the day will unfold. I often don’t finalize my workouts until I warm up and see how I feel.

I sometimes get ridiculed by other athletes (*Jackson cough cough*) for this seemingly haphazard approach. It’s certainly not for everyone and it was counterproductive for me in the past. It’s taken over a decade of personal and athletic development to acquire the self-awareness and discipline to make (mostly) good decisions operating with such an informal, spontaneous system. It’s a challenging balance to be fully invested in your process while maintaining the objectivity to intuit when and how hard to push and when to rest. I still routinely blow this and rely on my coach’s better judgement to reality check me. That said, I feel that this approach allows me to get more out of myself on a daily basis (whether it’s work or rest) than a more rigid, conventional training plan. My understanding is that this approach isn’t at all uncommon among top athletes.

It may be equally surprising that I don’t closely monitor training stress (e.g. TSS), total volume or threshold (FTP) and I mostly avoid formal fitness tests. Despite a very data-driven approach to each training session, I rely on more qualitative metrics to determine how I’m progressing and my “readiness to train”. It comes down to a few fundamental questions that I ask myself every day:

1. Am I accomplishing the essence of my training plan? If I’m constantly reworking my already flexible plan, moving the goal posts, making excuses, regularly blowing sessions or needing excessive, unforeseen recovery time, chances are I’m off track. You’d think this would be obvious, but I find it’s easy to slip into a self-deceitful cycle.

2. How’s my mood? This one is obvious. If I’m even more cranky than usual, some combination of overreaching, underfueling or lack of balance is often to blame.

3. How’s my sleep? Sleep is the single most fundamental factor governing my performance, recovery and mood. Sleeping well has long been a challenge for me and it’s an excellent barometer for my overall state. Overreaching, commitment overload and anxiety all tend to negatively impact my sleep.

4. How’s my sex drive? Stop giggling!! Like mood and sleep, this suffers when anything else is out of whack. Sex drive may be a decent proxy for hormonal health (specifically, testosterone levels for men), which is fundamental to triathlon performance, general health and well-being.

5. Am I on top of other things in my life? Training at the elite level is inherently single-minded, selfish and all-consuming… but not entirely. I’ve learned that if I’m scoring low marks at everything else in my life—my relationship, family, social life, home upkeep, other interests, even basic hygiene…—then my triathlon performance is soon to follow. Some amount of balance isn’t just necessary, it’s optimal!

Context & Periodization

I came into this block on the heels of back-to-back wins at IRONMAN 70.3 Victoria and Eagleman. After that demanding racing block, I took a week-long mid-season break with just a couple short swims and jogs. I’m a proponent of mid-season downtime to recover and get the most out of the next block, especially over a long (7 month) season like mine. Following my break, I used a local 750 m swim/5 km run race called Stroke & Stride as a rust-buster.

I raced less in 2018 than any of my four previous professional seasons—just seven pro races! Rather than attempting to have a dozen respectable performances like previous years, my intent was to hit the ball out of the park every single time. Putting more eggs into fewer baskets definitely carried risk, but also much greater potential for reward. The strategy payed off with wins at five of those seven races. I closed the season on a four race winning streak, undefeated over the full distance.

My training in this IRONMAN block was a departure from my usual approach to 70.3 training, which I outlined in 2016 (Part I & Part II). My 70.3 training tends to be fairly polarized for most of the year, with most training being pretty easy (Endurance/Zone 2) or pretty damn hard (VO2/Zone 5+) with middle intensities (Tempo-Threshold/Zone 3-4) used only sparingly. I maintained some high end sessions in all disciplines in this block, but accumulated most of my training load in the endurance range and also included more tempo and threshold than past blocks.

The nine week block leading into Mont Tremblant consisted of approximately a one week ramp up from my downtime, six weeks of heavy duty work and a generous two week taper. Following that race, I took a super light week before easing back into training. I took a full twelve days before reintroducing any running intensity. One of the most common mistakes I see athletes make is getting back at it too soon after a race. Patience is especially challenging following a particularly good race when you’re bursting with positive energy or after a disappointing one when there’s the temptation to beat up on yourself.

I discovered some of my best fitness of the year leading into Chattanooga. I kept my training in those intervening six weeks considerably lighter than the build to Tremblant. It’s taken me years to appreciate just how well I hold onto fitness. It’s a leap of faith, but I accepted that the hard work for Chattanooga was already done over a month earlier. My only objective before Chattanooga was to stay sharp. In my coach’s words, the intent was just to “ice the cake, not bake another layer”.

Related: How do Pro Triathletes Train? My Weekly Schedule: Part I & Part II

Volume

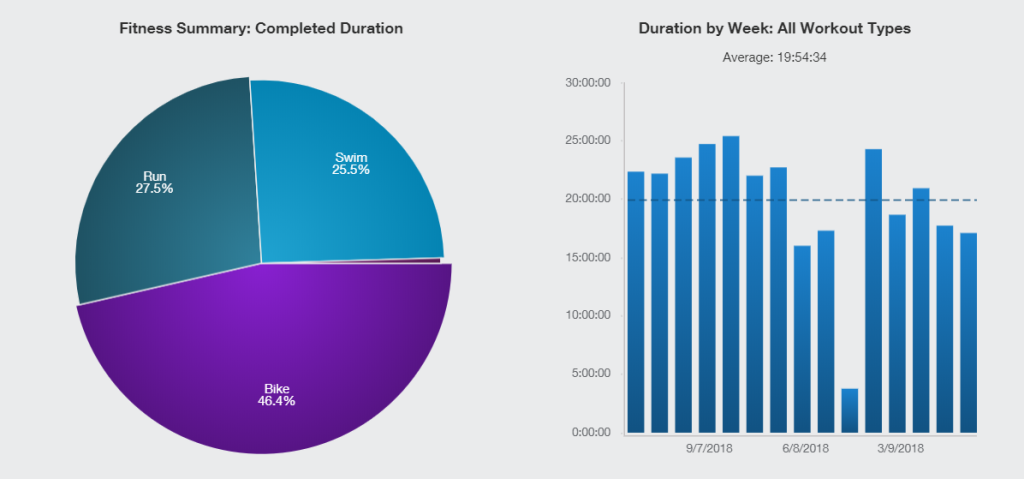

Reviewing my training, the most striking observation is that I averaged just under 20 hours per week during this period. That’s less than some amateur athletes train! It certainly doesn’t align with the common perception of elite IRONMAN training. I may very well be on the low end of the volume spectrum, but I feel that perception is skewed by a good deal of misinformation and hyperbole. Many pros will casually reference 30+ hour training weeks, but I’ve rarely witnessed elite triathletes consistently training around this level of volume. Few athletes can accurately tell you their average volume and instead tend to refer to their biggest, most badass weeks. Many athletes also seem to get a little creative with their accounting, rounding up and logging dubious “workouts”.

My volume may be relatively low, but my training load is more in line with expectations given the relatively high intensity of my training. Specifically, I tend to avoid the Recovery/Zone 1 intensity range that many athletes pad their training with to achieve those impressive sounding volume numbers.

Finally, I’ll point out that despite only training about 20 hours per week, this absolutely represented a full-time commitment at the limit of my abilities. I would caution anyone who may be tempted to try to copy my program. Not only is it specific to me, but keep in mind that my life is structured around training and recovery with other commitments deliberately minimized.

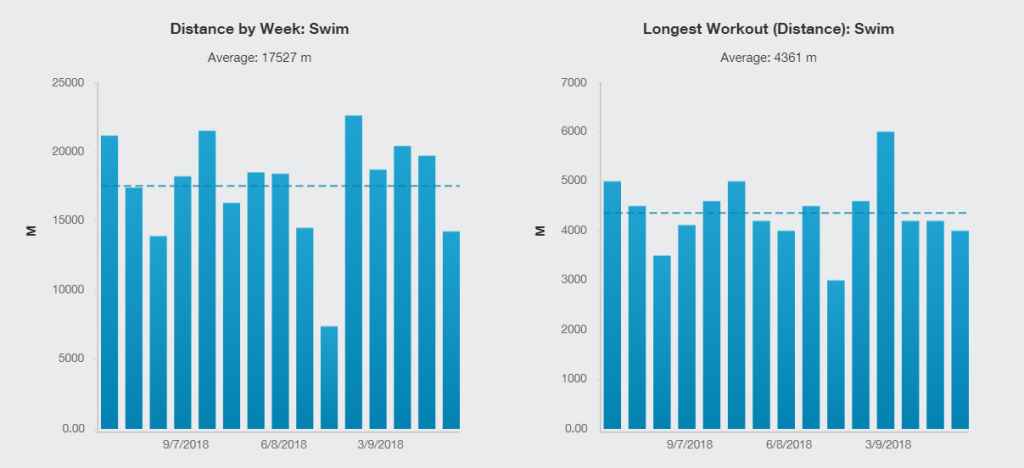

Swimming

During this 15 week period, I swam an average of just over 5 times and 17,500 m (range: 7,400-22,600 m) per week. My longest and shortest swims were 6,000 m and 1,400 m respectively. Swimming was on the back burner during this block compared to earlier in the year, when I swam up to 8 times per week (30,000+ m). I did the majority of my swims with Guelph Triathlon Project and swam occasionally with Loaring Personal Coaching Hurdle Project or on my own.

Swimming has always been the “canary in the coal mine” for me. What I mean is that it’s the first to show signs of fatigue when training load nears my limit. In fact, my swimming can get shockingly bad during a hard block, to the point that I’m 5 seconds per 100 m off my best times. I’ve learned that a brief period (a couple weeks) of subpar swimming at the height of a block may be an acceptable trade-off, but a month of poor swimming is a giant red flag.

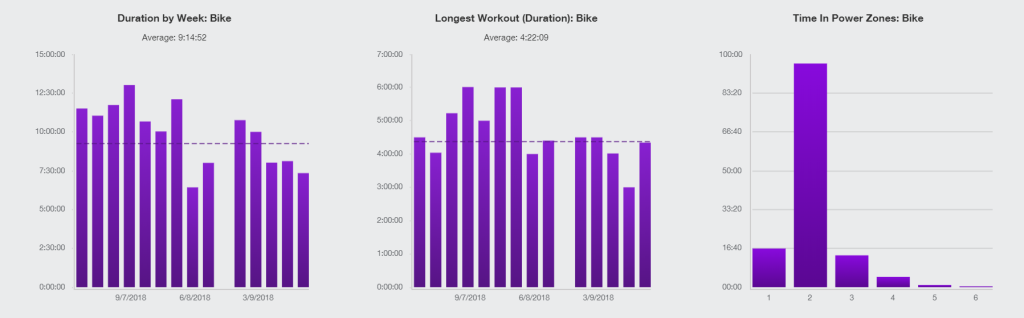

Biking

During this 15 week period, I rode an average of 3.5 times and 9:15 (range: 0-13 hours) per week. This frequency is pretty typical for my 70.3 training as well, though total volume was the highest I’ve sustained. My longest rides were three trainer sessions of 6 geological eons hours. I only rode my Ventum One tri bike during this block, though I’ve alternated riding with my cross bike in the past. The intensity distribution below (drawn from my Pioneer power meter data) shows that I spent the vast majority of my time in the Endurance/Zone 2 range which is roughly around 210-270 watts for me. I spent a smaller fraction of my time in the VO2+/Zone 5+ range compared to my 70.3 training, though I continued to avoid Recovery/Zone 1 (<200 watts). I typically did one higher intensity workout (Zone 4+) and one IRONMAN specific workout (~Zone 3) per week. I did most of my cycling intensity work and interval sets on tired legs after a long 2-4 hour lead up. This is particularly brutal, but seems to carry more bang for the buck in terms of adaptation.

I rode outside about once per week, usually a weekend long ride, which I consider the bare minimum. I spent most of my time on my STAC Zero Halcyon smart trainer. I prefer the trainer for many reasons including safety, precision and time efficiency. That said, the 6 hour rides were harrowing!

Related: How to Ride Indoors Like a Pro

Running

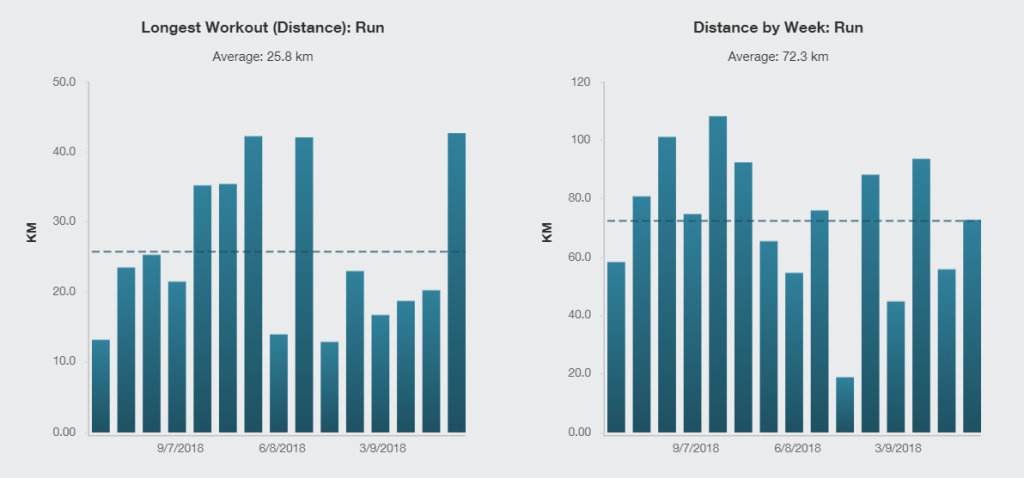

During this 15 week period, I ran an average of 6 times and 72 km (range: 19-108 km) per week, tracked on my Suunto 9 watch. This volume was similar to past 70.3 training blocks, but frequency was lower. During 70.3 training, I often run 7-9 times per week. The emphasis in this IRONMAN block was on fewer, longer runs. I did a few 50+ km double run days beginning with a hard 35+ km treadmill workout followed by an easy ~15 km afternoon trail run. The culmination of these long run days was a 2:45 marathon on the treadmill with significant pace variation about three weeks out from Mont Tremblant.

I did close to half my running volume on the treadmill. I consider the treadmill an indispensable tool, though it can become a crutch a times. I’ve learned that some amount of outdoor running is essential in order to translate fitness built on the treadmill to racing. I also used trail running both for the softer surface and also the cognitive and neuromuscular demands, since it forces you to focus despite fatigue.

|

|

|

|---|

Fueling

I won’t say much about my diet or race nutrition plan, because those are topics for future posts. You can find a summary of my race nutrition in my Slowtwitch AMA as well as some background info in this somewhat outdated post.

Optimizing the way I fuel training sessions was a major area for improvement this year. I have a history of underfueling workouts, undereating and disordered eating habits, which have come up often on my blog and in recent podcasts. To help manage these negative tendencies, I’ve come up with a system of rules around fueling workouts. For example, I always have a bottle with at least 100 calories of carbs/protein on deck during my morning swim. I’ll aim for 300+ calories per hour during workouts longer than two hours. I rehearse my exact race nutrition during some key IRONMAN sessions like long brick workouts. For other sessions, I use a variety of “real food” that’s full of fat, protein and fiber; nothing like what I take in on race day! I feel that this helped acclimate my gut to all manner of abuse so that, come race day, even my freakishly high intake of pure carbohydrate (~450 cal/hour) wasn’t problematic.

For the first time, I also experimented with a glycogen depletion protocol (aka fasted training) and strategic dehydration during a handful of key sessions. I would usually accomplish this by eating a good breakfast (500-800 calories), then swimming 60-90 minutes, followed immediately by a 35-42 km treadmill run. During these 3.5-4 hours of training, I limited fueling to just 100-300 calories of carbohydrate and 0.75-1.5 L of fluids. This would result in a deficit of several thousand calories and major fluid and electrolyte loss. I won’t delve into the research supporting this strategy. In essence, training in a depleted state like this attempts to mimic the demands of racing late in an IRONMAN and may provide some beneficial adaptations. The trade-off is significant: miserable workouts, compromised intensity and longer recovery time. There is some scientific literature supporting this strategy for certain athletes during specific workouts and phases of training. I’ll stress that this is playing with fire: high risk for minimal reward.

Conditioning

I have a rocky history with conditioning and strength training. It’s notable that I did next to nothing over these 15 weeks, just two 30 minute core sessions! This is neglectful even by my low standards. For better or worse, conditioning is always the first thing to go when I begin to struggle with training load. Throughout my history in endurance sports, I’ve alternated periods with significant conditioning work (i.e. weights, plyometrics, yoga) with periods of essentially nothing. There’s been no discernible correlation with performance, health or injuries (what injuries?). Conditioning has been a minor point of contention with my coach, who always advocates for more, while I never seem to make it a priority. In 2018, I maintained a consistent off-season routine (winter/spring) of heavy lifting, minimal plyometrics, core and yoga. Like most other years, this routine fell by the wayside once I began racing. The fact is that I won two IRONMANs doing essentially zero conditioning, though it could be argued that I was still benefiting from gym work earlier in the year.

In brief, the research on conditioning work making young, healthy triathletes faster is equivocal, but there’s a much stronger case for aging athletes and injury prone athletes. Many proponents of conditioning make their case based on anecdotal evidence, conventional wisdom and coaching experience, which shouldn’t be discounted based solely on what the latest half-baked research study concludes. I got back in the gym this off-season and I’ve been enjoying throwing iron around again. At the very least, I notice positive effects on my mood and body composition with an accompanying increase in regrettable selfies. Lifting may also counteract some of the insidious hormonal effects of high volume endurance training. That’s enough for me to renew my commitment to conditioning… for now.

|

|

|---|

Mental training

I devoted time to visualization during most of my hard sessions. For me, this isn’t as simple or pleasant as letting my mind wander aimlessly over my goals and dreams. My visualization process is more structured and effortful. I’ll replay key moments that I anticipate in upcoming races again and again and again in excruciating detail to the point of mental fatigue: making a pass, attacking a climb, going through transition, taking the lead, exiting the swim, etc. I force myself through this mental exercise late into my long workouts, when fatigue is mounting and focus is slipping. The process of continually dragging my attention back to a given moment is uncomfortable, akin to doing intervals with my brain. I feel that the payoff was that this helped me slip into a flow state for almost an entire IRONMAN, the feeling athletes refer to as being “in the zone”. Tremblant, in particular, had a surreal dreamlike quality, perhaps because I’d already rehearsed practically every aspect of the race countless times.

Meditation and mindfulness are becoming buzzwords in the endurance sports and broader wellness communities. I’m also increasingly hearing these concepts referenced by elite athletes. I’ve practiced meditation and mindfulness in some basic form on and off for years, but I still see tremendous untapped potential, both for athletic performance and to manage the crippling existential dread of being a millennial.

General health

This year went exceptionally smoothly, especially relative to 2017. My only illness was a cold after my last race in Chattanooga compared to a depressed immune system and incessant illnesses throughout 2017. I stayed injury free with the exception of a minor calf strain in January following a dumb-ass day demolishing my bathroom (no! not like that!). Stress levels were also far lower after moving into my new place in February and completing major renovations in June. A routine blood test in November following some post-season downtime showed my highest free testosterone and hematocrit readings. I don’t track weight or body composition too carefully, but it was clear that leanness and muscle tone reached a lifetime peak. I’m finally coming into my old man strength!

Consistency

It’s a cliché and a truism in endurance sports that consistency is key. This block was my most consistent ever with no major missed or failed workouts. The fact that I didn’t really do a single epic training day or workout is no coincidence. In my experience, epic training may earn kudos on Strava, but it’s not conducive to consistency. I drew confidence from my long runs and rides, not simply because I was capable of them, but because they were more or less unremarkable; I was able to maintain business as usual the day before and after without much impact on the rest of my week.

Check out Part II for details of every single training session leading up to these races.